Stagflation Threat in the UK ?

Stagflation fears

Stagflation is an economic term that had until recently been confined to the economic textbooks, with the major global economies having been immune to stagflation fears since the 1980s. As we have moved into 2022, however, economists, central bankers and market strategist have been quick to raise the spectre of the old enemy of stagflation.

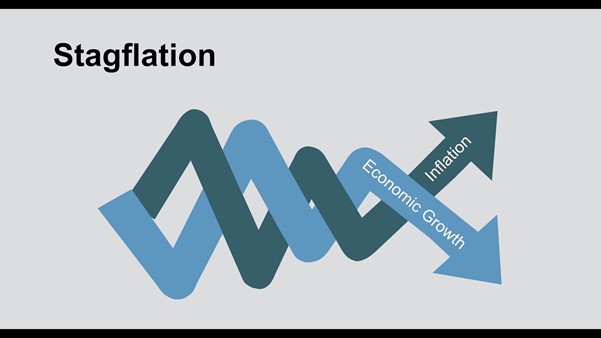

What is stagflation

The economic situation in which growth is slow and unemployment high is called stagflation. This term is used to describe a period where prices are rising while Gross Domestic Product (GDP) falls. The defining feature of stagflation is a period where there's slow economic growth and usually high unemployment or an unemployment rate that is rising significantly, which goes hand in hand with appreciably rising prices (i.e. inflation). It can be alternatively defined as an era during which both GDP levels decrease significantly while prices rise across all sectors—not just those related directly to raw materials or agricultural produce like food items.

Stagnation (low growth/ recession)

One of the attributes of stagflation is a significantly slowing economy, one where GDP is falling and even for the potential for a recession, economically defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth. Usually, however, an economic slowdown, goes hand in hand with low inflation rates, or even falling prices (deflation) as the total demand in the economy is contracting with GDP, putting downward pressures on prices.

Inflation (rising prices)

Conversely, increasing price rises and higher inflation rates are usually associated with periods of higher growth rates, when GDP is rising at or above the long run, optimal level. This is because stronger growth rates, equals stronger aggregate demand and as aggregate supply is slower to react to this increased demand, this puts upward pressures on prices, therefore inflation.

Stagflation in the past

Throughout the late 20th century and first two decades of the 21st century, stagflation has not been an issue, or even on the radar of economist and central bankers. This is because inflation has been at extremely low levels, in most global economies around or below the 2.0% level that many of the world’s major central banks target. This absence of inflationary pressures had been the case through the rapid expansions of the 1990s and early 2000s, as well as during the growth contractions and recessionary pressures from the global financial crisis in 2008 and from the Covid-19 pandemic from 2020.

However, stagflation was a real issue for central banks and governments in the not-so-distant past, with best examples coming in the 1970s. Up until then, there was a view amongst economists that there was an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment, describes by the Phillips curve. We are not going to go into detail of the Phillips curve but suffice to say that it describes the relationship we discuss above, that inflation and falling or negative growth do not often occur together. You can learn more about the Phillips curve here.

One of the main causes of the stagflation experienced in the 1970s was the 1973 oil price crisis and oil price shock. The spike higher in oil prices alongside the fall of the Bretton Woods system saw the global economy fall into recession, with the US and U.K. economies in recession from 1973 to 1975. During this period, there was also double-digit inflation, which peaked at more than 20%! The depth of the recession in the U.K. saw the introduction of the Three-Day week, which saw a state of emergency from 1974. Commercial users of electricity were limited to three specific consecutive days' consumption of electricity and electricity blackouts across the country were widespread (although essential services were exempt).

Clearly, the spectre of stagflation is one that central bankers, politicians and economists fear!

21st century stagflation threat

As we have moved into 2022, the word stagflation has featured more prominently in articles on the financial newswires, and reports from market strategist and economists. Having been subdued for multiple decades, global inflation rates were already on the rise in latter 2021. This was due to a number of factors, but primary owing to supply chain constraints and tight labour markets in the wake of the strong global recovery from the coronavirus pandemic.

The disruption to supply chains puts an upward pressure on prices, as bottlenecks in supply means goods and commodities are “bid up” as they are chased by consumers and corporates. In addition, the strong global recovery in the wake of the pandemic has seen shifts in the labour force, with many individuals not retiring to the labour market. This has seen many global economies moving back towards or at full employment, which creates a tight labour market and puts upward pressures on wages and potentially in turn onto prices.

On top of already increasing upwards price pressures across commodities and goods has been the invasion of Ukraine by Russia and the significant upwards pressures on commodity prices. This has not only been confined to spikes higher in Oil and Natural Gas, but also seen metals, and agricultural prices surge higher to multi-year and even record levels.

Although the world’s major economies have not yet seen notable decline in GDP or rises in unemployment, the threat going into 2022 and beyond is for the negative impacts from the Russia/ Ukraine conflict alongside the increasing inflationary pressures to push many of the world’s major economies into a significant economic slowdown or even recession. Given the high inflation levels, this notably raises the threat of stagflation.

Stagflation threat in the U.K.

From the perspective of the U.K. economy, the Bank of England (BoE) has already raised interest rates three times in this new cycle, by 0.15% in December 2021.then twice by 0.25% in February and March, up to a current Bank Rate of 0.75%. This has been in reaction to surging inflation and in particular food and energy prices. It could be argued that compared to many of their global counterparts, the BoE has been the most aggressive and hawkish of the major central banks.

However, the U.K. economy is far from safe from the threat of stagflation, with inflation running at a 30 year high at the time of writing (the February CPI data published on 23rd March was at 0.8% month-over-month and 6.2% year-on-year). With the threat of stagflation looming, the threat is for a still more hawkish tone from the Bank of England into 2022.

Author: Mr Steve Miley - Senior Investment Consultant